|

Alberta Street Gallery is home to six jewelers, all of whom create their works differently- from materials to design. For artist Mandy Allen, aluminum is her medium of choice, and before you begin imagining soda cans, think again! Aluminum is a metal which can be transformed in a myriad of ways: from 2-dimensional framed wall decor, to 3-dimensional sculptures, to mix metal collage-like designs, as well as jewelry. Mandy’s work transforms sheets of aluminum into sculptural and jewelry forms that have a flow not unlike Art Nouveau designs. Mandy took classes in metalworking at a high school magnet school, but her higher education moved her from Los Angeles to Humboldt State University in Northern California, to study with David LaPlantz. When she speaks of this period of her education, you can feel the excitement for aluminum art. She explains that she learned many jewelry-making techniques, not just those which focused on aluminum with LaPlantz, but she felt drawn to metals and especially colored anodized aluminum. She has worked in this medium since 1994. After Mandy graduated, she worked part-time in jewelry manufacture, but she soon decided to set out on her own. Her love of aluminum art bloomed into a full-time, self-employed jewelry business called “Mandy Allen, Metal Arts .” Upon arriving at Mandy’s home, she guided me to the basement, which serves as her studio space. We toured a small room off to the side, where she keeps the chemicals she uses to anodize and color her aluminum before it is cut and sculpted for jewelry. The first part of Mandy’s process is focused on treating the metal as a solid sheet before cutting, shaping, and assembling elements. Anodizing aluminum is a chemical/electrical process. The purpose is to make the aluminum stronger and to create a porous surface that will absorb color. In order to anodize, the sheet of aluminum is submerged in an acid bath (see image) with electrical current. The current stimulates a chemical reaction, forming an oxide layer that helps not only with the coloring, but also giving the aluminum a resistance to scratching and marring during the cutting and forming processes. After the aluminum is anodized, the next step is adding color. Vats filled with colored dyes (see image above), specifically made for this process, sit alongside the anodizing bath. The aluminum is then dipped in the dyes to add color. The dye absorbs into the aluminum quickly and, depending on which color dye, can be finished within minutes. Overlapping colors can be added to create a new color or pattern. For some of her botanical pieces, Mandy uses sponges in various shapes, dips them in a different colored dye, and then places them on the piece for a few minutes (see image below). The aluminum then absorbs that color on top of the original dye used on the sheet. Finally, the dyed piece is boiled in distilled water for one hour, which sets the color in the aluminum. Once the color is set, Pieces are cut or punched from the anodized sheet metal to create the desired shapes. Mandy manipulates the shapes with hammers and pliers into their final forms (see image above). At the end the piece has been hardened for durability when worn. Aluminum can’t be soldered like other metals, so all elements are assembled with “cold connections.” Small circular links called “jump rings”, rivets (a form of kinetic connection), and wire-wrapping are her most common connections. One of the benefits of these cold connections is that they permit a great deal of movement when the piece is worn. She uses niobium for ear wires due to their hypoallergenic properties. Silver - both fine and sterling, is also used. The wire and chain are also either fine or sterling silver. She specially sources her chain, ensuring it is made in the U.S. and clasps are all hand-fabricated. Every aspect of her art reflects a thoughtful, well-educated, and inspired approach that cannot help but capture the imagination.

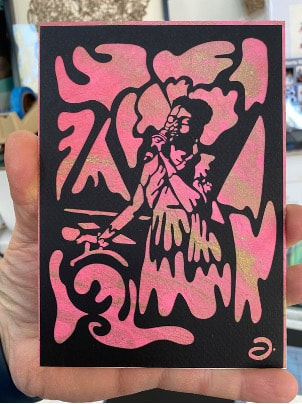

In terms of design, Mandy explains that her inspiration was originally rooted in Chinese and Japanese textiles with botanical motifs. Today, Mandy reflects on her earlier work and considers new approaches for old designs. Her current work crosses both Mid-Century Modern and Art Nouveau with some geometrics but with flowing lines which are so commonly seen out in nature. Pieces have a feeling of geometric flow that is complex, while seemingly simple. Her work ranges from small, simple earrings to more elaborate designs with many elements. Each design is feminine and elegant, with that beautiful pop of color that gives the metal life! Paper art is a medium that is wide-ranging, often involving many techniques. Artists who work in paper arts might employ methods such as cutting, folding, layering, curving, bending, stitching, and so forth. David’s contemporary work uses cutting as the primary technique employed, but there is much more to the process of paper cutting than the name implies, which I quickly discovered as I toured David’s NE Portland home and studio. As I was shown around his home, I learned that not only is he an artist, but he is also a collector of art. David has works from his early years in Chicago and New York, to newer pieces he’s appropriated since moving to the Pacific Northwest. His appreciation of art extends beyond paper art to include painting, photography, and even sculpture. It’s when he shares the work of other talented paper artists. His passion for the process and ultimate outcome brings a wide grin to his face. Upon heading to his studio which is a beautiful converted garage with a skylight, window and glass rolling door - his sweet dog Poppi comes to greet me. Rarely do you see David without Poppi at heel. His time with her is clearly a source of inspiration for his art, as the piece “Dog Park” exemplifies. There is more to paper cutting than what you might think. While sitting in the evening, David will work on “one-liners”, as he called them, where he sketches images by moving a pen along paper without stopping, joining the starting and ending point of the line together, then shading in the solid area created by that one line. This is a template for possible future work. Alternatively, when he has a custom design requiring the joining of many subjects or a more elaborate subject in mind, such as the “Dog Park” he will use Adobe Fresco on his iPad. This gives him the ability to join many disparate people, objects or words together. While not every design he creates results in a finished work, spending 2-4 hours each night creating designs provides him with a vast pool to pull from whenever he feels inspired to produce a new artwork. His work ranges in subject from the personal of daily life, to political themes, to the natural world, and more. On occasion, his designs are custom work of people, pets, or even events; more about custom work can be located on his website under “commission”. Ultimately, when asked what his style is he states that he is an “eclecticist” and that “we only have one life to live and we try to do as much as we can.” It is this approach that creates a body of work that is accessible to everyone. No matter what you are interested in, you are bound to find a piece that speaks to you and your lived experience. It wasn’t until around 2010 that David began paper-cutting. While at Powell’s Books, he saw and bought a book on paper cutting. His early pieces used a colored, handmade paper background with a black-cut design on top, leaving the negative space to take on the color of the paper behind (See Image, above). Over time, the handmade and colored paper fell into disuse, as he created a new approach to adding color and shading to his layers. This adds brilliance, as it relies on the reflective value of color added to the backside of his cutting onto a white background. Prior to beginning, David adds colored paper to the backside of the black paper he will cut. He then transfers his design onto the backside, where the colored paper is glued, as his guide for the blade. His blade then meticulously follows the lines of the design to create the cutting and is prepared for mounting onto the white background. Mounting typically uses clear plastic “stilts”, which are small cylinder pegs (See Image, below). These stilts are glued to the backside of the cut design and then finally to the white background. If the cutting were directly connected to the white background, the color that is attached to the backside of the black cutting would not be visible. It is the stilts that keep the cutting raised from the white background, allowing the illumination of the backside color through ambient light that produces the color used in his pieces (See Image, Below). You can see a time lapse video of his process on his website. The finished piece is typically framed in a shadowbox frame, which holds the entire piece as a single, finished work of art. Viewed from a distance, the color or colors used on the backside of the black cutting bring life and movement to the cutting’s image. With a wide range of knowledge and experience creating, one thing is clear: we cannot wait to see what he dives into next! An array of past and current work can be viewed on David’s website. David is currently open to commissioned work. He has completed custom pieces to commemorate large events, pets, friends or family, and other themes. You can contact David about a commissioned piece on his website.

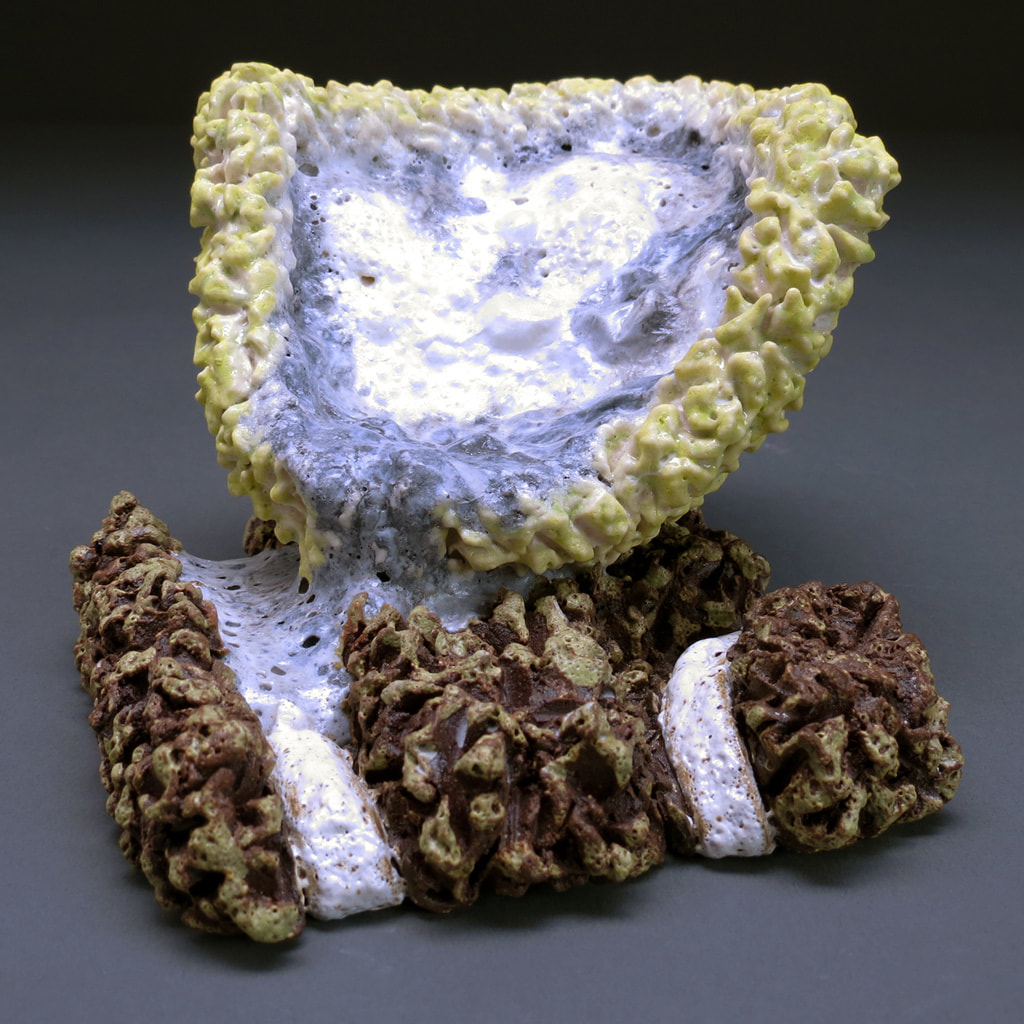

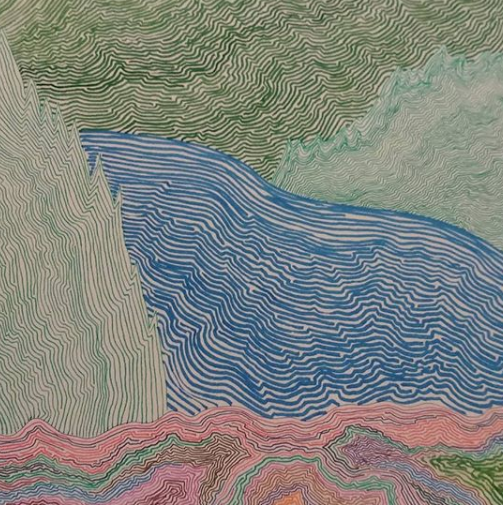

David is also on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. Follow along to keep up to date. Journeys in FiberThere is no playbook for how to create what they envisionedIf you wanted to create a meticulous, life-like image of a mushroom or of a piece of bark, in what medium would you work? Would clothing scraps be your first choice? If you were planning on recreating a photograph of a favorite place, would you fall back on using pieces of vintage Japanese kimonos to build it in layers and layers of said fabric? Well, this is what our artists of the month do. While you could refer to their creations as “fiber art,” upon closer examination, it is so much more and ultimately more complicated. Kim Tepe is a costume designer by trade who had the idea to recycle scraps from her workplace at the time, to create her art. Alycia Allen Tolmach started out as a journalist, but left that field almost 30 years ago to embark on her own creations. What is common to both artists is that they have created their own techniques along the way. When an idea pops into their heads, both are extremely innovative in trying to find a way to make it happen. Sometimes it's about applying an existing approach in a novel way or with slight modifications. But if there is no playbook for how to create what they envisioned, they are writing it along the way. Journeys in Fiber indeed! Moving Fiber Art Forward Alycia creates her landscape art quilts working from photographs she has taken from her travels, mostly in Europe, using a collage technique with fabric. “Unlike most landscape quilters, I don’t fuse my fabric down first before I sew it. I cut it and pin it and appliqué it with a free-hand zig-zag stitch.” Many landscape quilters tend to fuse elements made up of cut-up pieces so everything stays in place and nothing moves when the element is being manipulated or stitched. Early on, Alycia took a class that involved fusing and hated the results, which were “stiff and flat, with no life to them.” “What I do is called ‘raw-edge’ or ‘bad girl’ appliqué. I don’t fuse anything. I cut pieces out. I layer them on my design wall, pin-baste them with straight pins and zig-zag around with a sewing machine.” This produces a very different result. In Alycia’s words, “It lets the fabric billow and breath. It is soft and pettable and catches the light. It comes out touchable.” And she does it all using almost exclusively fabric from vintage Japanese kimonos dating back from World War II to the 1960s. But more on that later. "Instead of painting with paint, I use fabric and thread" Kim started as a quilter but as she says, quickly left that world. “I am trying to recreate moss, lichen on bark, things you find on the forest floor. I collect bits of bark and lichen and try different things to recreate it.” Of course yarn and fabric are always in the mix, and she is trying to find different fiber art techniques to recreate specific textures. Where she ended up in her quest might surprise you. “I took craft felt, painted it and hit it with a heat gun. As it turns out, this process makes great bark! I painted Tyvek and melted that. I’ve experimented with a shibori technique, putting buttons into fabric, knotting it tight and boiling it. I use wet felting as elements. I work the wool and water use my hands to shape it until it felts.” Since she never needs a lot of any one thing, she is a regular at ScrapPDX where she finds materials for her inspirations. Adds Kim, “I try and find things, as opposed to buying new. I just need a little bit, a little square that has the right color and texture.” It shouldn’t come as a surprise that it is difficult to put a label on such a creation. “Sometimes I say that instead of painting with paint, I use fabric and thread,” explains Kim. “But now, my new creations are no longer flat. My wall pieces are dimensional and I also started creating 3-D sculptural pieces.” Central to Alycia’s art is the fact that she is working in vintage Japanese kimonos that she takes apart and makes into smaller pieces. “Each is spectacular in its own way. There are designs that glow, have different weaves, distinct dying and painting techniques. Sometimes, the back looks completely different from the front.” The way she sees it, “the fabric is magic! it has a life of its own; it contributes.” Using typical commercial quilting cottons would pale in comparison. “This particular fabric is like a silent partner that adds so much life to my art.” An Extremely Labor-Intensive Process Kim’s goal is it to recreate something natural in fiber. While at times has worked from photographs or pictures, she now mostly gets inspired by bits and pieces she finds on the ground in the woods. She is a perfectionist who wants you to be surprised that what you are looking at is fabric. “For me, the biggest compliment is somebody asking me how do you preserve the pine needles on your fabric? I don’t; it is all fabric. But people think I used the real thing!” she explains. “I want them to be drawn to it from afar and be amazed when looking at the stitches. I really want to share it with people, because it is so different.” Not surprisingly, the most fun for Kim is “when all comes together and it works. When I found that technique that works, having people in the gallery look at it and stop and wanting to touch it.” Kim started out doing landscapes but is now firmly into creating perfect tiny worlds. Just look closely at one of her mushrooms sitting in a batch of moss and you’ll understand. “There is a lot of hand embroidery; there are endless hours of tiny knots. I like it, very zen.” Alycia’s landscape art quilts are created from layers and layers of kimono silk. Working from her own photographs, she builds her landscape from the horizon or sky forward, always keeping a keen eye on the proportions to ensure it will look as realistic as possible. “I have to get the proportions in the background right and more importantly the tones. If the scale of the background is too big, or the colors too bright, by the time you get to the front, everything is wrong and you have nowhere to go,” she says. Every one of her pieces is built up in that way. “I can have a sky that is made up of seven layers of transparent colors. In some places, there can be 10 layers. There is sky underneath the buildings, mountains behind the trees.” This adds to how approachable her pieces appear. “I encourage people to touch my art, to feel it. I want my pieces to be touchable and want the fabric to feel really nice.” And she goes on saying, “I am trying to share a sense of a place that struck me as really special -- and maybe my take on it is not the traditional take, but it is something that touched me. By recreating that in fabric, I am trying to add to that, integrate how I felt when I was there and what kind of person I was then. I am trying very hard to recreate that moment in time. And, to tell a story as well.” Conveying the story, the things that one cannot see but form in the mind of someone looking at her art are equally important. She succeeds when people cross the threshold that is often between the piece of art and the admirer of art. “What makes me happiest is when people reach out and touch my quilt. It is a physical manifestation of what I want to have happening: I want the quilt to touch them.” Like Kim, Alycia puts in a lot of thought and effort into creating her art. Because her quilts often depict architecture as well as countryside, she is constantly making up techniques as she goes to meet the challenges. Numerous rounds of trial and error occur before something is how it was imagined. Alycia knows she has succeeded when “the decisions start coming easier.” She explains that “there is usually a point where I absolutely hate the piece. Getting over that, is like a big sigh of relief. There is a point where it just starts to work and it is just getting better. That’s when I am in the zone and decisions are right and happening and it just keeps getting better and better.” Art and Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking

This chapter title is the title of a book by David Bayles and Ted Orland. It’s one of the sources Alycia falls back on for encouragement. Neither one of this month’s artists can name distinct individuals or artists who influenced them. In fact, both for a very long time doubted their own capabilities. Alycia admits that she has had a lot of dry spells when she was out of the studio or when other things took precedence in her life. Still, “even when I am not working, I am thinking about the process or the particular problem that I am having with a piece sitting on a wall. And now, I’ve figured out a sustainable way to work, so I expect to be much more productive.” Kim recalls that she had doubts about calling herself an artist. “For a long time, I didn’t identify as an artist because I use a lot of craft techniques. I doubted that what I do is real art. I think sometimes that I walk a thin line between art and craft.” For Kim, it took “just a level of confidence and acceptance” to come to the conclusion “that what I do is art.” For Alycia, one of the biggest things she had to try to overcome is “that I am a real perfectionist and that can be very paralyzing. I try to make each piece spectacular and that makes it hard to experiment and be willing to fail. Working smaller is the answer for me; and continuing to push through even if it feels like you have no talent whatsoever.” Being part of the Alberta Street Gallery, surrounded by other artists, has been really inspiring for her and helped her in her work. No Rest for the Weary - Always Trailblazing Kim started experimenting recently with a process called eco-printing. She combines natural fibers, leaves and natural dye. When rolled tightly and steamed, the image of the organic material transfers to the fabric. For now, it’s part of her scarves. Eventually, she would want to cut out those images and stitch them onto her sculptures. For now, “I need to perfect the printing process first.” But you can be sure that she’ll figure it out eventually. Alycia’s next challenge is creating the water in a waterfall quilt. Depicting water and waterfalls is common in quilting but she hasn’t seen one yet that truly impressed her. In 2014, getting ready for an art show in California, she was trying to finish a quilt of a waterfall set in Nice, France. When it came time to create the water itself, “It looked so hokey. But I was out of time and we had to get in the car and go! So as soon as we got home, I took off the ‘stupid’ water, and the quilt has been waiting on the wall ever since.” Now, 5 years later, she says, “I think I have figured it out but I have since learned that I need to experiment on smaller quilts first, to perfect and master the technique. Which is what every other kind of artist does, but it has taken me years (and the Art and Fear book) to give myself permission to work small, play, fail, start over and not have to have each quilt be the be-all and end-all of my abilities.” Figuring out how to work smaller has been a revelation to her, and she is very excited with her new work, which she can complete in weeks or months. Large pieces, like her waterfall, sometimes percolate over several years. But regardless of the finished size, “there is a lot of contemplation that happens in my art; it’s not a straight start-to-finish process.” And for a good reason: “My art is a way for me to live on in somebody else’s life after I am gone.” Moments of AweBeauty in imperfect materials, in nature & how to capture everythingWhen June Martin sits down at her table to create art, she works with parts that are smaller than Abraham Lincoln’s head on a penny. On the other hand, Gary Grossman is dwarfed by standing in his art and most likely spent a few hours in his car getting there. Gary is a landscape and wildlife photographer. June specializes in micro-mosaic art, applying its techniques to create distinctive earrings, bracelets, pendants and rings. When everything comes together “I have always been a keen observer and deeply affected by the environment around me,” explains Gary. “Being in the presence of a wild animal or a great landscape when the light is right is awesome and life-affirming and fulfilling. I am trying to capture that both for myself and hopefully to share with others.” It’s a moment of awe when “the elements come together: Subject, composition, light. When all of it comes together like tumblers in a lock.” “I look for ease and harmony,” says June. “If I can fit things together that way, that is great. I learned that if I can’t, if I torture it, it just doesn’t look good.” If people walk away from her art with a sense of being pleased, if they admire the colors and texture and have an appreciation for detail, then she knows she has achieved that harmony. Her goal is to help people “see the art in it” and not “just pieces thrown together.” Gary strives to get people to “feel inspired about the natural beauty of the earth, and the animals and creatures in it, and to work to protect and conserve it.” For him, art is a celebration of the natural world and human beauty. Either in the world outside of us or within, art is life. June adds that “art feeds me. It is my calling; it feeds my soul.” She feels very lucky to be able to live off her art and works tirelessly to have enough pieces for the various galleries that display her jewelry, and for the Saturday Market, where she is a regular. For Gary, art isn’t what pays the bills. With now-grown children, he finds that he has finally more time for photography, but still it is something that is mostly relegated to a weekend. “Now ... I am finally able to give in to what is clearly an ongoing need. I need to be out in nature exploring,” he explains. Becoming an artist Gary grew up in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. He spent a lot of his adolescence outdoors, first trout fishing and then more and more taking pictures. When his work was shown in college newspapers, “it became a lifelong hobby.” He continued taking pictures and hanging the work in his house for friends and guests to see. What surprised and motivated him was the fact that people liked it, some even inquired how to purchase his photographs. “I got the idea that what I do could have broader appeal than just for my own personal pleasure.” On a trip to Bangladesh, he took pictures and the West Linn Tidings wrote a story about it. That led to an exhibition in the West Linn library. Eventually, he noticed Alberta Street Gallery and applied to join the cooperative. “It’s very fulfilling to share my work with others and see them appreciate it.” Even so, he is not sure about the moniker artist. “I am a translator of natural beauty on to the printed form.” And, as Gary points out, “photography has a long-running debate about whether it is a craft or art.” June has always had something to do with art but was also pushed to learn a profession that would allow her to make a living. Looking at her success, one wouldn’t think it was a roundabout way that led her to where she is today. Initially, she learned shorthand and how to type to be able to support herself as a secretary if needed. She worked in the design department of a retail clothing store and more recently finished an education as a therapist. “When I was a kid, I used to say that art is how I would earn my living. It just didn’t happen right away.” For June, the moment she realized that she was an artist happened only four years ago. “I always had to do something artistic but then only recently took it very seriously,” she says. “Everything shifted once I realized that I wanted to do art every day. Things happened to me in a sense that my work started to support my ability to do art. I didn’t have to have another job to support me. Now that my art is self-supporting, it just makes it easier to be more creative because I can focus. It has taken on a life of its own.” For that, she is “thankful and humbled.” Inspiration

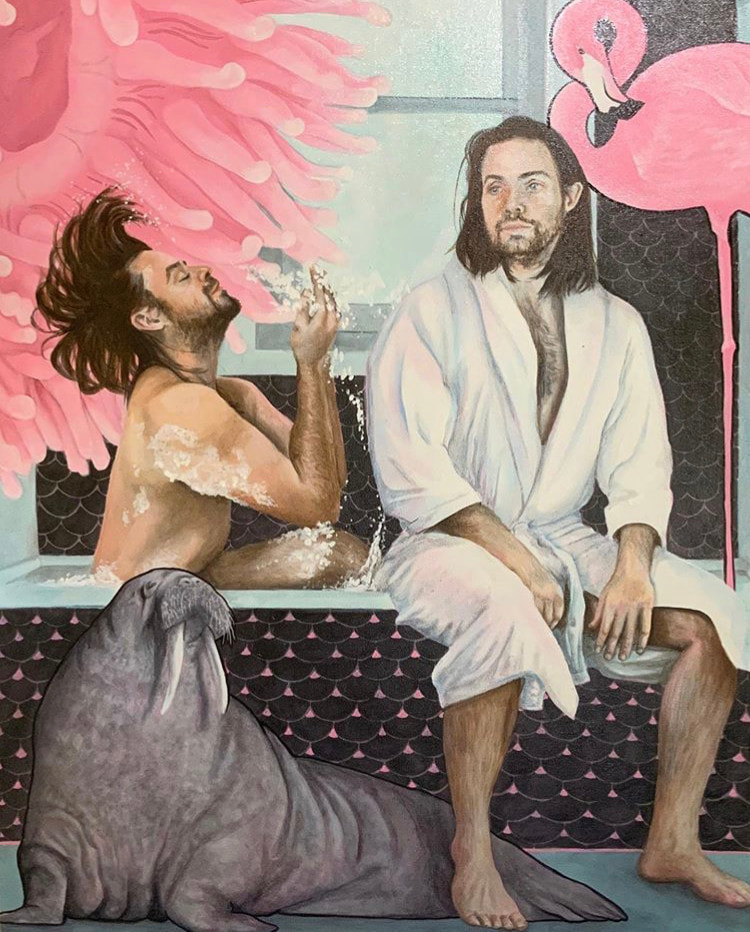

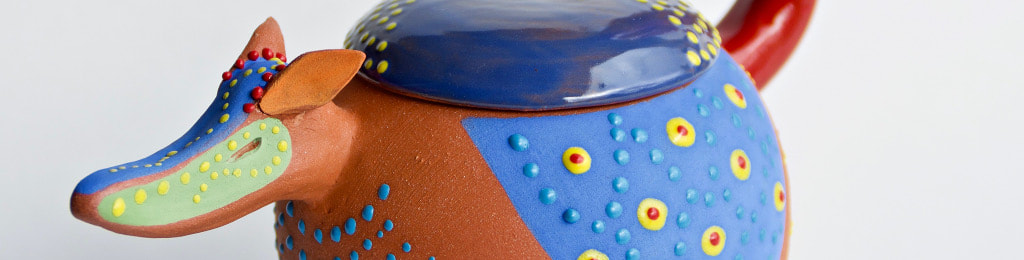

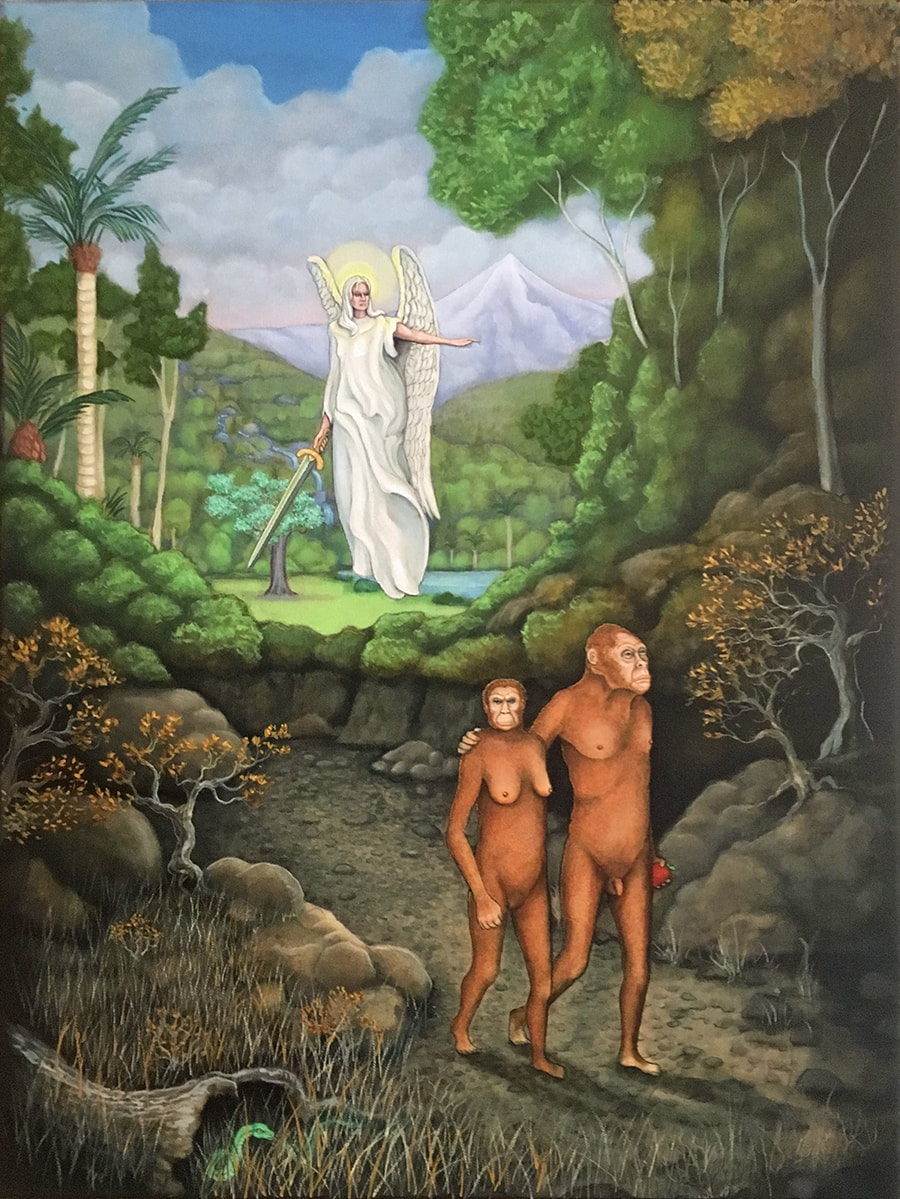

Looking at June’s art, one can see the influence of the landscape and colors of the Southwestern United States, Costa Rica and Mexico. “The colors and textures, and the light is different in those places.” She is influenced by Mark Rothko, Frank Lloyd Wright, Wassily Kandinsky and German expressionism. Sometimes, people trace elements of color and structure from these sources to her jewelry and mention it to her. “That makes me very happy.” Before all else, Gaudi and his work in Barcelona was a great inspiration. So much so, that she went on an impromptu trip to the city and spent a month very carefully studying everything. “Back in the US, I wanted to learn how to do mosaic and so I took classes.” While initially she did larger mosaics, she soon had the idea to combine micro-mosaic techniques with jewelry making. “A modern twist on an art form that has been around for hundreds of years, but mostly depicted floral designs and landscapes.” Looking at Gary’s landscape photography, the influence of Ansel Adams is visible. Although Gary also worked in black and white at one point, he is now “addicted to color.” “The world is colorful. The more color the better, as long as it is realistic.” Realism is also what he strives for in his art. He explains that he loves the creative process, finding and memorializing that special moment. And, he seems to have a great sense for it too. “I usually know at the moment of capture. There are these serendipitous moments when a scene presents itself, when fog lifts or settles. Something that wasn’t there before suddenly appears. Sometimes something is fleeting. Capturing that moment is a feeling of elation.” He says he almost always knows that this is going to be great shot. Adding, “I live for those moments!” You might encounter Gary and his Canon 7D Mark II in the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge about an hour north of Portland. He also loves Bandon, Oregon, for its scenic beauty, Yellowstone for wildlife and landscape and the Zumwalt prairie in Eastern Oregon. “It’s beautiful high country with great vistas and, by the way, the largest population of breeding raptors in North America.” June gets materials for her art from a variety of sources. “My tile I get predominantly from Morocco and I love, love, love it. She also uses specialty glasses from Italy (i.e. Millefiori and Filati). She explains that the Moroccan tiles come cut to her but that she has to cut them down further or shape them. “Pieces are sometimes only 3mm long and so I am sitting there with rubbing stone or rotary nippers that cut tile and glass, making everything even smaller.” She says that she has the most fun “when I find color compositions that I haven't done before. Trying and playing is great.” While she is getting her pieces cast mostly to keep costs down, she fashions all her own ear wires and jump rings. She adds, “My main focus in on the actual mosaic.” Looking back and forward June realizes that it took a windy path to get here. “In retrospect,” she adds, “I would have liked a more direct path, but didn’t believe in myself enough. So [if you are an artist starting out] believe in yourself and just do everything you can if that is really your goal to make it happen. And also build a community, enjoy the community and surround yourself with people who are making it happen in your life.” After some reflection she adds, “Do all that without starving.'' As mentioned before, Gary had to wait for a point in his life to be able to devote serious time and effort to his photography. His advice to budding artists is to “Stay the course,” and “Keep working at your craft.” “Don't let the idiots get you down.” He also puts value on views from the community: “There is nothing quite like feedback from other artists and the public.” Other than in galleries, he also frequents online communities like Flickr, Instagram and 500px to look at the work of others and get inspired. (Sur)realismo Mágico“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.”This is how the French writer André Breton describes surrealism in 1924. This month’s show at Alberta Street Gallery is called (Sur)Realismo Mágico because of surrealist elements in Katrina Zarate’s work and the “realismo mágico” of Verónica Arquilevich Guzmán’s clay figurines. Both artists take inspiration from a place that is different from the reality we all experience, and they also blur the lines between dream and reality in their work. André Breton would have been proud. Sources of Inspirations Growing up in Mexico, Verónica learned about the spirit animals, alebrijes. These creatures are based on real animals but have features or elements that make them new, unknown, fantastical. The artform goes back to Pedro Linares in the 1930s. When he was lying in bed severely ill, he saw strange things in his dreams and later replicated them out of cardboard and papier-mâché. If you have seen the movie Coco, it is filled with alebrijes, including the dog with wings. For Katrina, inspiration came from a true nightmare: an eye condition that seriously threatened her sight. Several surgeries later, her eyesight had improved but “these issues with my eyes solidified how important art is to me and gave me the impetus to do it while I still can.” Paths to Becoming an Artist One of the biggest questions that every artist must answer for herself is where to get inspiration. What is the reason to create art in the first place? Where does the drive to be creative originate? In life, it can come from unlikely places that are not always positive experiences. The strongest force in Katrina’s creative drive was when she experienced serious issues with her eyesight. “Because both my (retinas) detached and tore, I had to have a number of surgeries to repair the damage. That is why the way I perceive reality today is different from what it was. I was nearsighted and had LASIK surgery. The complications that followed were cataracts and then being farsighted. And now, one eye is nearsighted and one is farsighted. I still have blind spots in my vision and sometimes lines are wavy. My brain compensates but not always. And, by moving through different vision perspectives, ‘I saw’ how different the same thing can be, and how it affects our perception and representation. “I started painting when that happened and watched my art change and be affected by how my vision changed. For instance, I gravitated to bold, impactful colors from having a cataract and having to work through the cloudiness. Bypassing my eyes and working through experience has taught me how to paint and create representation,” says Katrina. She is quick to add that while this was a serious life experience, she is happy where she is today and how it has enriched her life. Verónica says that, “When I was a young kid, the only thing I liked to do was drawing and painting. But I never knew that there was a career opportunity. I studied graphic design with a focus on advertising. But when I worked in an advertising agency, I didn’t like that as much, so I started to do art.” She also started teaching others. “I emptied my dining room and made it into a classroom.” While she lived in many countries around the world since, it was only when she came to the US, that art became more central in her life. She created her own exhibitions and continued teaching children. “I needed to convince myself in the first place that I am an artist , and that art is what I should be doing. Only if I believed it, other people would as well.” Before Portland, she lived in Dallas and Santa Barbara. “In Santa Barbara, I had a couple sponsor me. They were interested in the variety of my style.” says Verónica. “In that moment, I realized that this is really happening. I thought to myself, you can be a real artist here.” Still, things weren’t easy, but she persisted. “I was cold-calling in my broken English. I was knocking on doors until I found the door that was open. Life is full of opportunities everywhere, but some people just don't take risks.” Living in many countries, Verónica always painted what she saw, but she really started focusing on ceramics while living in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The many different cultures in one place were “almost like a culture shock. I couldn’t focus on what to paint. It was too much,” she explains. Both artists were also inspired by what their respective fathers did to earn a living. Verónica’s father was a biologist who “gave us that sense of respecting nature and to love it. With my pieces, I try to get people to love and respect nature.” She lists nature as her greatest influence. How Katrina’s father influenced her is most visible in the window display. “My dad is a writer and director in the theater world. The staging and stage design that happens in my compositions come from there. Growing up with him being rooted in the world of theater really influenced some of my compositions.” Creating Andre Breton’s “Absolute Reality” Here is how Verónica describes her art. “[It is about] my heritage, my roots, the colorful element that is in the Mexican culture. Earlier, my pieces were nature, plants. If you bring together nature and plants with the Mexican colorful element, you get what alebrijes are to me: Fantasy, animals that don't exist. An iguana with wings. The imagination of a child. I try to imitate (the colors and the patterns this art form uses,) but I do it in clay. Alebrijes traditionally are done in wood.” Katrina started out as a portrait artist painting as close to reality as possible. You wouldn’t think that if you saw only her current work, which is more surrealistic. “I am taking pieces from other series that I used to do. I play with reality, color, line, dimension, scale,” she explains. “Through the years, I have been playing with one concept and one field of art, and I created a number of series of similar paintings, like the one of “dogs and beer.’ But now, I look at those series that include portraiture, pop art, strong lines, abstraction; and work on ways to combine them with realism.” The result is an enticing mixture of styles such as the realistic portraits of local musicians in front of an abstract background. “I am working with some things that are 3-D or 2-D, I experiment with scale - blow up or shrink elements, and with putting elements together in an interesting way. It’s an abstraction. Close to pop-art style at times.” Verónica describes her ceramic alebrijes as “playful, colorful, nature-inspired. They are decorative but can be usable too. One of my creations is a bowl-like creature where the tail is a spoon. It could serve as a container for salt, salsa, etc.” In fact, one of the characteristics of a traditional alebrije is that parts of the animal can be removed. Planning - An Important Part of Creating Verónica wants her art to be an “inspiration about loving and respecting nature. And about having a sense of the Mexican culture.” The former is one of the reasons she is now focusing on working in clay, after many years of painting in a variety of media. She gets the most fun from “the wheel, from working with clay. Creating ‘the thing.’ ” Later, when she has to paint it, it is more difficult for her. “I have to do a lot of planning. But the coming out of something that is nothing -- that’s so cool. Something that connects you to nature. Clay is such a strong connection to Earth.” Conversely, the most fun for Katrina is when the underpainting is complete and she gets to build transparent layers on top of it. “When that happens, it takes that thing from this good but not great thing, to that bigger, more realistic, deep canvas. It transforms from a flat painting to a real piece of art.” Even though Katrina’s art looks lighthearted, “everything I do is pretty planned. I create my version of what things are going to be. I start with a sketch and lay out what the composition is going to be. I build an underpainting and then add multiple transparent layers of paint. It’s pretty meticulous work, pretty thought-out. It’s all planned. Some artists ’just go’ -- I am not that kind of artist.” She describes her style as “weird” (laughing). She adds, “I enjoy playing with styles, so it is hard to narrow it down to just one. I am not a ‘this’ artist. My art is the most Portland art.” She wants people to look at her work and “leave with a sense of joy, to be inspired to be creative and to laugh.” Being an Artist For Katrina, it is clear that “everyone should make art, but not everyone should make art a career. It’s a hard life. If you can do anything else and be happy, do that thing. But if you can’t, then do art and do it as hard as you can do it.” “Creation is a form of meditation,” says Verónica. For any artist, it is important that you “believe in yourself and focus on what you really, really want to do and do it.” She made that commitment for herself. “Me and art is like one thing. I don’t see it as a role, or a part of my life. Rather, it is something that cannot be separated. If I am not doing it, I feel that I am not doing what I am supposed to be doing in this life.” Just as important to her is teaching art, especially to children, because it teaches them about themselves and builds self-esteem. Katrina describes the role of art in her life succinctly: “The entire thing. Literally my whole life. It is all of it.” However, she admits that she never wanted to be an artist. “Because I grew up with my dad and his life as a creative person, I knew how difficult it was to be an artist. The challenge was clear to me and daunting. So I tried to be everything but.” Life experiences changed everything. Today, “when I am not painting, I am not OK. It’s a coping mechanism. I tried and can’t do anything else but being an artist.” Katrina is also firm in the belief that if you are an artist, it’s paramount to learn the business of art. “That is important and an ongoing process.” About real reality, fake reality, and divergence pointsWhen you first notice one of the abstract photographs by Dan Bernard, your mind goes from recognizing the familiar to realizing that it is now something else, or something in addition to what it is. bd dombrowsky’s paintings draw you in with cheerful colors and images that evoke an expectation of what you will see but once you’re close, you have to realize that what you see is a snarky reality, a caricature of what you were expecting. This month’s featured artists are experts in playing with reality, and in tricking the mind of the observer to create something new. Here is how bd describes his art: “I think of my work as allegory painting. I like to tell stories. I want to create the essence of a story that is open so a person can bring their own part of the narrative to it.” The viewer is essential to the story that is about to be created. “My work is like a carnivorous flower. You get pulled in from a distance by friendly colors and images, and once you are there, it’s too late, you’ve seen it.” For example, you might think of it as a religious painting but then from close up, it is a snarky social commentary. For Dan, “abstract is an image that makes you ask what is that? It is often something that cannot be identified. It’s a detail of a texture, or something ordinary taken out of context. It becomes interpretive, and very personal. It becomes much more than any other photography because it is selective. I select a piece of something that intrigues, isolate a part and create a world onto itself. The process of abstracting allows each viewer to project their own interpretation onto the image.” Omitting color enhances this effect. “Black and white images always fascinated me because it is not a literal interpretation of life. Rather a more interpretive visualization that allows me as the photographer to manipulate it, interpret it, to put my own fingerprint on it.” The particular use of the medium Dan’s focus is on landscape, street, and abstract photography. His contributions to the July exhibition are mostly photographs he took on a recent visit to Zion National Park.”I felt like I was in my temple,” says Dan. “Such a spiritually moving environment. The quiet but visually and geologically dynamic elements of the landscape are mind-boggling. You are sitting there and see over geologic time. You notice the earth-shaking things that have taken place.” Looking at elements that got pushed up by seismic or volcanic activity but are now frozen in time is an experience that he describes as “dramatic and magical.” In order to capture a great street scene, “one has to capture ‘the decisive moment’ as Henri Cartier-Bresson put it." That is when movement, people, contrasts converge to create a fascinating/interesting moment to observe. “I am greatly influenced by him,” says Dan. Doing street photography is similar to “hunting”, because one has to “blend in with the landscape, be invisible, to catch that convergence.“ bd works in oil on panel. “Panel makes a solid substrate that I can prime and sand to a smooth state. That then allows me to draw cleaner lines and push out paint as far as I want. I use a “classical method” creating a monochromatic underpainting in umber tones and then apply layers of glaze over that. With the brown underlying, the use of thin oil paint, and glazing, I allow light to go through the layers of paint to the panel and come back up.” He sums up his style as “illustrative, with a pinch of surreal.” When asked about his style, Dan describes it as “moody, dramatic, revealing, particular.” His goal is “to push past, break through the limits of what my style has been in the past; to surpass, exceed my style as I develop a new facet of it.” A great example are the new abstract images that he has developed for this exhibition, adding double exposure to his repertoire of tricks. “Standing on the shoulders of giants”

This thought by Isaac Newton is very much applicable when talking about who influenced this month’s artists. bd mentions Rene Magritte, Yves Tanguy, Ron English, Edouard Manet and Caravaggio. He also loves Salvador Dali’s paintings but his “personality annoys me.” From Magritte, it’s “the non-sequitur quality of his surrealism. Taking things completely out of context.” Tanguy has this “ability to create the impression of a story or that some things look like they are real but are not. He plants seeds of things that look like real things but don't exist.” Caravaggio is an “amazing painter. His application was so gorgeous. He put religious themes in (at the time) contemporary images that allows people to connect on a very visceral level.” Other than the Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dan is greatly influenced by Ansel Adams’ landscape photography. “I learned about photo-chemistry from Ansel Adams. His books “The Negative”, “The Print” -- I read and reread those multiple times. I was obsessed. That is how I learned how to develop film and control the medium.” For Dan’s abstract photography, he looks to the work of Edward Weston. One of Weston’s great achievements is taking the ordinary and making it remarkable. Abstract pictures of bell peppers. Or, taken straight on, a close-up of the toilet bowl making it appear very sensual with its curves and white porcelain. Another influencer is Andre Kertesz, a Hungarian-born photographer who is now considered one of the seminal figures in his field. The creative process bd works on several paintings at the same time. “I have them around the house and stare at them. Meditate.” That is his way of trying to find out where a painting “needs to go”. It’s a “slow, transactional process.” The most fun for bd is actually painting. It evokes memories of coloring. “Drawing is like riding a bike uphill. A challenge every stinking time. Painting is the fun part, riding downhill.” For Dan, it is “when I share my work with others and find that they are moved or inspired by what I created.” He describes that feeling as “exhilarating and addictive” and likens the making of art to an addiction. “The longer I am not doing it, the less meaning my life has. And as I re-engage to create, my sense of purpose grows. Sharing is the peak — emotionally and spiritually. When the moment is past, the process restarts.” While he is always his first critic, he also posts frequently on Instagram and judges from the reaction of his many followers how well-liked a photograph is. Dan hopes to “evoke in others the feelings that I experience when I see art and hear music: Exhilaration. Hopefulness. I want to inspire them, perhaps to create their own art. I dream that my creations will leave an indelible impression or memory, just like the art and music that I admire”. For bd, creating divergence is central to his art. “How things start out from one point and go different directions.” At times, he takes an old painting of his and recreates it, adding another layer of abstraction. “It’s now not only divergent from a story but also from itself. It’s double divergent.” It shouldn’t come as a surprise that both feel deeply about art. Art for bd “is my entertainment, my therapy, and my job.” Adds Dan, “After family, it is the main organizing principle of my existence.” Advice to budding artists “Create. Create. Create. Art. Art. Art.” is how Dan sums it up. bd is as black and white in his view: “Dive in or quit. Only do it if you can’t not do it.” Both Dan and bd are experienced artists. bd has exhibited his paintings all over San Diego and Southern California, has participated in solo and group shows in many cities and also shows in places like restaurants and coffee shops. He is also a regular at the Portland Saturday Market. Dan, in addition to being a photographer, is also a musician in his own right. If you’re lucky, you can catch him performing at the Gallery, most notably during his and bd’s Last Thursday opening reception in June. Art Inspired by Movement Picture a group of snowboarders carving up a mountain, leaving a variety of lines in the snow. Even after they are gone, the traces they left are testament to the dynamic movement, energy, and the fun they had. Now, picture a bicycle in a street race. Individual spokes are disappearing because the wheels are turning so quickly. The gears are spinning similarly fast and all you are able to see is a blurred image of what you know is a gear wheel. Getting inspired by fast movements, capturing what these do to their surroundings, freezing a fleeting moment in time -- that is what both of these artists do so beautifully in their art. Brian Echerer’s sculptures are made out of gears and spokes, the very elements that are so dynamic when in use, but now forced by him into permanent positions. The surface of some of Ian Wieczorek’s ceramic pieces shows deep fissures, crossing and intersecting with each other. They might as well have been carved by mini snowboarders coming down the sides in a wild race of bliss. It is a manifestation of both artists’ deep love for different sports that is influencing their artistic creativity. Sport Begets Art Brian Echerer was an avid bicycle racer who participated in road races, mountain biking and cyclocross.”My art is cycle-centric and an expression of my passion for cycling. But to me these pieces are no longer chains and gears. It’s like a different medium now.” Bicycle art has been around for a while. People have created bracelets out of spokes for example. Brian at one point realized that “you can do so much more with it.” He added decorations to his spoke bracelets and started selling them at the Saturday market, on Etsy, and other places. “I am lucky in that if I can imagine something in my head, I know I can make it come to life.” Not surprisingly, Brian prefers the term “maker” over “artist.” Self-taught, he has been constantly expanding his skill set as his visions became more elaborate. “When I needed to learn how to weld in order to create my vision, I watched YouTube videos and learned from others how to do it.” He did the same when there was a need for soldering, for glass pieces to be incorporated into his art. “Often it’s trial and error,” he adds. “Even as a child, I was always taking things apart and putting them back together, learning on the fly.” Ian Wieczorek explains that “my sculptures are drawn from my experience with action sports. It’s all about fully living in the moment, being hyper-focused on what I am doing.” He transfers that “meditative state” into the studio, where everything is in a state of flow and he just creates and responds. Creating ceramics is a hands-on, almost “sensual” experience. “I particularly like that clay displays different characteristics in the different states of creating ceramics. Initially, it’s wet and malleable. When dry or after a firing, I get to use a different approach and tools to continue making the piece into what I envisioned.” Working with glazes and the chemistry behind it “engages the nerdy folds of my brain,” he explains. In contrast to the intuitive process of creating the sculpture, when glazing, he needs to be very precise with measurements and temperatures,“ otherwise the piece is a brown pot and not a vibrant sculpture. And it’s fun to create unique glazes that complement the different textures and forms. It keeps things fresh.” Life’s Double Takes

Both Ian and Brian very much appreciate being a part of the art collective where an artist can hang his or her art for much longer than in traditional galleries. They also cite the opportunity to exchange ideas and learn from other artists as yet another element that the gallery brings to its members. It’s funny that Ian and Brian are having a show together because of how their artistic lives intertwine before. Ian joined the gallery in October of last year. He lives nearby and walking on Alberta Street, he noticed a few people painting the walls in a store and putting finishing touches on what is now our new gallery space. He walked in, started a conversation, and ended up jurying into the art collective. Brian, on the other hand, is one of the main reasons that the gallery looked at this space when we lost our lease in the old location. He and Maquette (one of last month’s featured artists), in different ways, were instrumental in negotiating the terms, getting people excited about this opportunity and making it finally happen. About Art and the Process of Making it “I would describe my style as simple, classy, chunky,” says Brian. Indeed, all elements are visible and uncluttered. Not pretentious at all. When asked the same question, Ian describes his style with words like “flowing,” “expressive,” “texture,” “movement” and “gestures”. No surprise that he draws inspiration from interviews and clips of snowboarders talking about their passion for the sport. Brian early on was influenced by his parents and an uncle who all are artists in a variety of artistic endeavors. Ian says that “I want my art to provoke a spark of energy, curiosity and imagination. And the impulse to touch the textures.” He looks up to progressive ceramic artists like Ken Price, Peter Voulkos and Ron Nagel. He admires how these artists have been changing how people look at pottery; from something that is “pretty” and “decorative” to a contemporary place that is edgy and expressive. When making art, Brian is fascinated by the fact that he “can visualize a piece in my head and make that. It’s almost mystical. To envision something and bring it into the real world as an object.” When asked what he wants people to walk away with after seeing his art, he says “the art” and laughs. Seriously, he loves seeing people’s reactions to his pieces. In fact, it was a strong reaction of a person at his stand at the Saturday Market that made him realize that he is an artist in his own right. It took persistence on his part and that is also his advice to young artists. “If there is a will, there is a way. Persistence will win the day more times than not.” For Ian, the most fun about creating art is “getting in there and making.” To be in a studio, listening to good music, enjoying the company of other artists and getting lost in discovery. His advice is “Chase your curiosities; who knows where you will go. Because mine have taken me around the world.” Blurred Lines at Alberta Street GalleryApril’s Last Thursday opening sets the stage for a month-long view of two very different artists at Alberta Street Gallery. One of them, Maquette Reeverts, has been with the gallery for more than a decade and works primarily in acrylic and oil. The other, Ray Andresson, is a recent addition to the group of 30 artists and has been with the gallery for only nine months. He showcases his abstract and mixed-media drawings. For Maquette, Blurry is Beautiful Maquette draws inspiration from photographic mistakes that people make, whether that is cutting off the heads of their subjects or taking blurry photographs. The latter is what she has been focusing on for the last few years. “It’s all based on light and how light goes through the lens of an SLR. I started as a photography teacher in high school and saw a lot of photographs with obvious ‘mistakes,’ but that made them also interesting. Not necessarily wrong, just different and something new,” she explains. “I am fascinated by how light works from going through a lens.” Maquette has an art history background and finds inspiration from a wide variety of styles and the work of many artists. It’s that breadth that influences her, more so than any one artist or group in particular. When asked about what is the most fun for her when creating art, she explains that “I really enjoy seeing the difference between the photograph that inspired me and the finished piece of art. It’s kind of a private pleasure since I never exhibit the two side-by-side.” Inspired by Nature, Microscopic Organisms and Landscapes While Ray’s earlier work was more pattern-centric, he now gravitates towards nature and organic subjects. Talking about his process, Ray explains: “Sometimes it takes me two or three months to finish a piece. I’ll stop when I run out of steam, then I pick it up later, and let it rest again. It takes me a good month on average before I feel that a piece is finished.” For inspiration, he often looks at images in books and online and the work of other artists. While he took a lot of art history and studio art courses that also influenced his work, Ray points to the Russian painter and art theorist Wassily Kandinsky as his strongest influence. ”You cannot look at linear perspectives without the person that invented it. One of the assignments in a painting class was to pick a song and paint it. Kandinsky was a pioneer who tried to visualize music in his art.” He adds that the best part of creating a work is “not knowing how it will look like when it is finished.” The Role of Art in Their Lives Both were drawn to being creative since they were children and never stopped. As Ray points out, “Paraphrasing Picasso, every child is an artist and the trick is to stay one as one becomes an adult.” He worked in a variety of media over the years. “I really like ceramics. I did mixed-media sculptures with found objects. I also tried a little bit of jewelry.” But for now, “at a very basic level, the kind of art I am doing now is in part driven by affordability and accessibility of the material.” He adds that even during the darkest times in his life, he has always had an urge to create art. For Maquette, the importance of art also cannot be overstated. “It is at the very center of my life. I try to live a creative life, also in other things that I do and get involved with. It’s noticeable in my home, sometimes in what I wear.” Advice to Budding Artists “Keep practicing! Don’t let anyone pigeon-hole your work and where do you want to go with it,” says Maquette. Ray adds, “Most importantly, don’t take rejection or failures too personally.” Both stress how important it is to do what you love and look for inspiration everywhere, in life, other artists, books, and online. Why Alberta Street Gallery? “One of the main advantages of a co-op gallery is that your art is continuously up,” explains Maquette. “You change it out, but it is not rotating off the floor as in a traditional gallery.” “Most galleries are businesses that profit off an artist’s work and provide space only,” says Ray. “The co-op model is very different because everyone contributes to the success of the gallery, the operation, and the direction it takes.” |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed